When you are a little girl with a big brother, you assume that they are some sort of adult. By the time you have become a teenager, they might refuse to be seen outside with you because you wear bright colours. You have access to more music and literature than your peers, though.

When you’re middle aged, after your parents have died, you might find some common ground. We both disliked phone calls, so there were text messages for the last few decades. Mostly these referred to the weather, with a lot of colourful descriptions of hospital appointments over the last couple of years. Allegedly, if you’re unable to get to a hospital two counties away at the crack of dawn, you’re not taking your illness seriously enough. When people are unable to walk very far, it’s unlikely that they could board a train. It’s also unlikely that any public transport system will deliver them to a distant hospital very early in the morning.

There must be thousands of people trying to take their ailments seriously, yet still being criticised by overworked receptionists. Maybe it’s a plot to make symptoms worse and speed up the patients’ deaths?

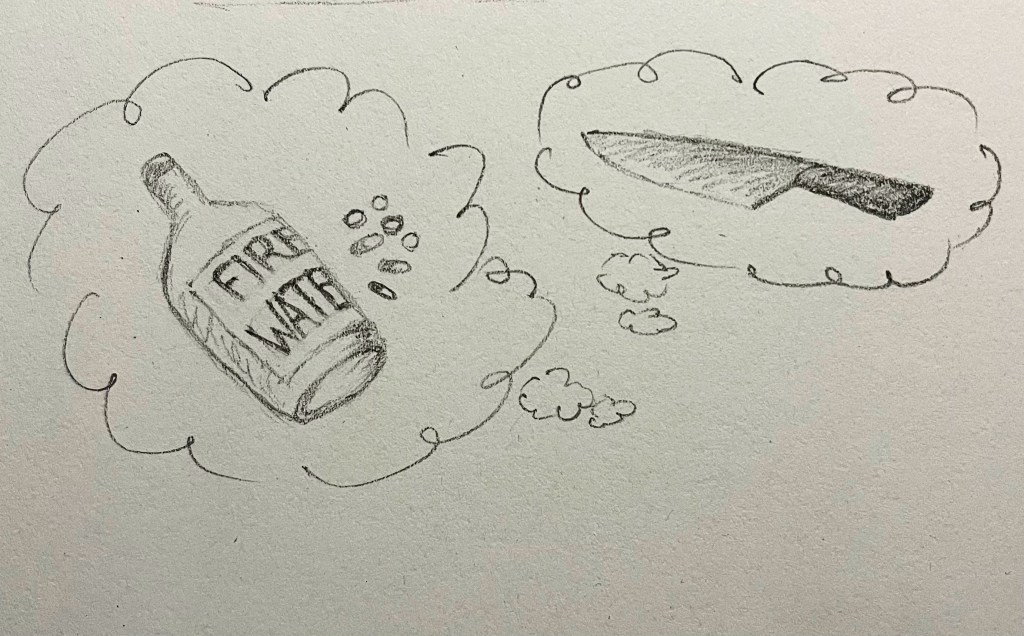

Observing my brother’s end of life experience brought to mind Roger McGough’s poem Let Me Die a Youngman’s Death. I might plant some more poisonous plants in the garden for future use, rather than waiting around for any indignity at the end.